C-TRAN could operate for nearly three years without taxes

John Ley

For Clark County Today

“Cash is king” one often hears in the world of business. C-TRAN has been adding cash to its balance sheet, while Portland’s TriMet is burning cash at an unsustainable rate. TriMet appears to be on track to burn through nearly $1.1 billion in the next decade. Ridership at both agencies is well below pre pandemic levels.

C-TRAN recently published its 2023 Annual Report. The agency showed a significant increase in the number of riders using the C-Van and Current “demand response.” Hours of service increased nearly 20 percent for demand response. This service primarily assists senior citizens and handicapped individuals, although the Current offers point-to-point service in five areas around the county.

Regular bus route ridership numbers increased by a smaller amount, as hours of service increased by 4.7 percent. Overall, C-TRAN had 4.2 million annual boardings last year. That is an increase of over 400,000 from 2022, but 29 percent below pre pandemic levels in 2019. Ridership peaked in 1999 at 7.75 million and has been in decline ever since. The transit agency does not include numbers by route, nor for its cross river “Express” service into Portland in the Annual Report.

Financially, C-TRAN is doing well. It has $423 million in assets on its balance sheet, up $62 million from a year earlier. This is up from $119 million a decade ago.

Net operating costs are $69 million. With $205 million in unrestricted cash, C-TRAN could operate its transit service for nearly three years without any tax revenues or passenger fares.

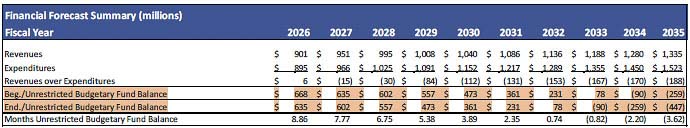

Contrast this with Portland’s TriMet, which expects to burn through nearly $1.1 billion of cash reserves over the next decade, according to its 10-year financial projection. A year ago, the projected cash burn was $485 million. The agency received $669 million in federal aid from 2020 through 2022, which it completely exhausted to forestall layoffs due to the pandemic.

This is extremely relevant as the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBR) is demanding a $2 billion, 3-mile MAX light rail extension into Vancouver, as a form of “high capacity” transit service. Included in that proposal is a demand by TriMet that new taxes be imposed on Washington residents to help pay for the alleged $21.6 million operations and maintenance costs of light rail.

Federal Transit Administration (FTA) rules only allow the federal government to pay for up to 50 percent of capital costs of a new transit project. Therefore Washington and Oregon will have to find $1 billion of the $2 billion proposed cost of the light rail extension. It appears Washington taxpayers are on the hook for $500 million.

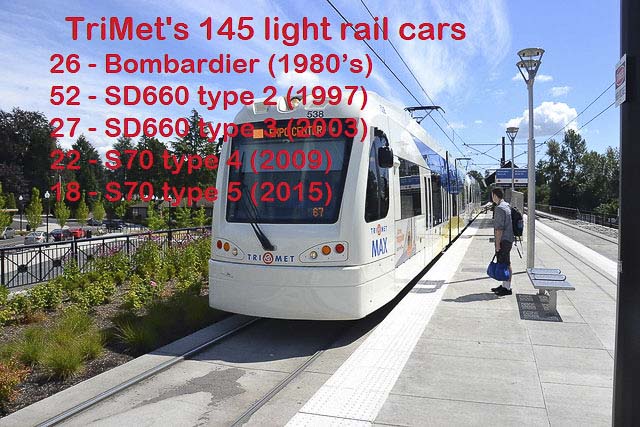

TriMet is also demanding Washington taxpayers help pay for 19 new light rail vehicles to replace a similar number at the end of their useful life. The IBR proposal includes a major upgrade to TriMet’s Gresham Ruby Junction maintenance facility, in addition to a new “overnight” facility at Expo. In 2012, forensic accountant Tiffany Couch found $50.6 million was budgeted for the maintenance facility, 16 miles from the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) site.

The FY2025 TriMet budget expects passenger fares to only cover 8.5 percent of operating expenses. “Passenger fares are down significantly compared to pre-pandemic levels by nearly 50 percent, which is a direct reflection of current ridership,” the report states.

Of importance to taxpayers, C-TRAN passenger fares only cover 5 percent of operating costs for regular bus service. The sales tax area residents pay covers the other 95 percent of costs. In 2019, passenger fares covered 14 percent of costs. A decade ago, farebox recovery was 22.7 percent.

C-TRAN spends $12.16 per passenger on its bus service, and $69.24 per passenger for demand response. Last year the average C-TRAN bus carried 15.6 passengers for each hour the bus was in service.

Nationally, transit ridership is in decline. The pandemic lockdowns accelerated the decline. People able to work from home have limited the “recovery” in transit ridership, post pandemic.

Charles Prestrud of the Washington Policy Center recently discussed the national trend in declining ridership. “Transit ridership dropped sharply with the onset of the COVID pandemic in 2020,” he said. “The slow rebound in the years that followed has prompted discussion, sometimes in hushed tones, as to whether transit had entered a ‘death spiral.’”

Prestrud notes transit agency revenue in Washington state has increased substantially, from $2.15 billion in 2012 to $5.19 billion in 2022. Yet productivity has fallen. In 2012 bus service in Washington state averaged 31.4 passenger boardings per service hour, but by 2022 that had fallen to just 15.96 boardings per hour.

Prestrud notes: “These trends show that transit in Washington state is not in the typical ‘death spiral’ of decreased revenue leading to service cuts leading to lower ridership. Rather, the problem is that costs are spiraling up while productivity has been trending down.”

A decade ago, C-TRAN carried 24 passengers per hour of service. Today it is 15.6. Operating hours are up nearly 4.5 percent from 2014, while passenger boardings are down 30 percent. Passenger miles are down 52 percent.

At TriMet, the problems are worse. Bus service has 118,740 average weekday rides, versus 182,837 pre-pandemic rides, a 35 percent decline. For MAX light rail, the decline is even worse. They report 69,310 average weekday rides versus 120,923 pre-pandemic rides, a 42.6 percent drop.

An additional financial concern for Clark County taxpayers is TriMet’s significant unfunded employee pension liability. While some modifications have happened in the past decade, TriMet is accepting a partially funded pension plan to keep its financial problems from being even worse.

“TriMet’s funding policies target a funded ratio between 80-90 percent rather than the normal target of 100 percent. The funding objective for TriMet’s two defined benefit pension plans is to maintain an adequate funded status while avoiding the accumulation of a trapped surplus. For this purpose, a plan that is at least 80 percent funded based on the market value of assets will be considered to have an adequate funded status. As reported in the FY2023 audited financial statements, the non-union plan is 86.6 percent funded and the union plan 78.0 percent funded.”

How much of TriMet’s pension liability do Clark County residents want to pay?

Portland metro voters rejected a $2.9 billion major light rail expansion in November 2020. They didn’t see the value in the 11-mile Southwest Corridor Light Rail Project. One suspects they would also reject a $2 billion, 3-mile IBR light rail extension, if they were allowed to vote on it.

Clark County voters have rejected light rail multiple times at the ballot box; 1995, 2012, and 2013. The Washington legislature killed the $3.5 billion CRC in 2013 due to tolls, light rail and wasteful non-bridge related pork-barrel spending.

One might ask, where are the elected officials or community leaders who will protect taxpayers this time? With the $7.5 billion IBR proposal now behind schedule and promising increased costs, can citizens afford a project that will provide no traffic congestion relief, at triple the cost?

The IBR has projected 26,000 to 33,000 average daily transit boardings on the I-5 corridor by 2045. Those numbers have received significant scrutiny. It appears to be a number created arbitrarily to try and justify the $2 billion light rail portion of the current $7.5 billion proposal.

Prestrud closes his “death spiral” column with the following.

“Even though the transit “death spiral” has been dodged for the time being, the question of how to efficiently provide mobility looms ever larger. It has also become clear the conveniently optimistic assumptions and forecasts in the plans of transit and regional planning agencies are no longer valid. Updating those plans and their underlying assumptions so they reflect actual trends is urgently needed. This is not a situation where transit’s increasingly serious performance problems can be wished away.”